Drug which extends life of mice hints at longer, healthy old age for humans

In our ever evolving journey to search for the fountain of youth it seems as if some really impressive strides have been made recently. In a collaboration between NUS Medical School in Singapore and the Medical Research Council Laboratory at Imperial College London a study has been done which extends

The life of mice by up to 25%. The mice that were treated lived for an average of 155 weeks, compared with 120 weeks for the untreated mice in the control group..While these findings are only in mice, it raises the tantalising possibility that there could eventually be drugs that would have a similar effect in elderly humans.

Scientists at the Medical Research Council Laboratory of Medical Science at Imperial College London found that switching off a protein called IL-11 increased the healthy lifespan of mice. In humans, levels of this protein increase as people age, and past research has linked it to a number of conditions associated with ageing, including chronic inflammation, disorders of metabolism, muscle wasting and frailty. Professor Stuart Cook, who was co-corresponding author, from (MRC LMS), Imperial College London and Duke-NUS Medical School in Singapore, said:

Research Council Laboratory of Medical Science at Imperial College London found that switching off a protein called IL-11 increased the healthy lifespan of mice. In humans, levels of this protein increase as people age, and past research has linked it to a number of conditions associated with ageing, including chronic inflammation, disorders of metabolism, muscle wasting and frailty. Professor Stuart Cook, who was co-corresponding author, from (MRC LMS), Imperial College London and Duke-NUS Medical School in Singapore, said:

“These findings are very exciting.Researchers found that the treatment largely reduced deaths from cancer in the animals, as well as reducing the many diseases caused by chronic inflammation and poor metabolism, which are hallmarks of ageing. Essentially, the animals lived healthier lives for longer, and according to the findings, there were very few side effects”

The researchers performed two experiments.

The first genetically engineered mice so they were unable to produce interleukin-11

The second waited until mice were 75 weeks old (roughly equivalent to a 55-year-old person) and then regularly gave them a drug to purge interleukin-11 from their bodies

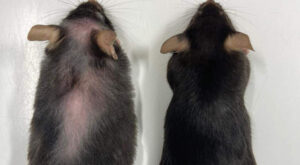

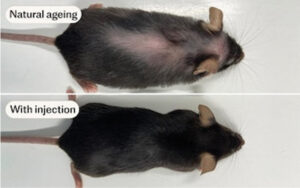

The results, published in the journal Nature, showed lifespans were increased by 20-25% depending on the experiment and sex of the mice. The treated mice were known as “supermodel grannies” in the lab, because of their youthful appearance. They were healthier, stronger and developed fewer cancers than their unmedicated peers. The quest for a longer life is woven through human history. However, scientists have long known the ageing process is malleable. For example, laboratory animals live longer if you significantly cut the amount of food they eat. Old laboratory mice often die from cancer, however, the mice lacking interleukin-11 had far lower levels of the disease. And they showed improved muscle function, were leaner, had healthier fur and scored better on many measures of frailty. The treated mice also had stronger muscles, better lungs, skin, hearing and vision than their untreated counterparts

The results, published in the journal Nature, showed lifespans were increased by 20-25% depending on the experiment and sex of the mice. The treated mice were known as “supermodel grannies” in the lab, because of their youthful appearance. They were healthier, stronger and developed fewer cancers than their unmedicated peers. The quest for a longer life is woven through human history. However, scientists have long known the ageing process is malleable. For example, laboratory animals live longer if you significantly cut the amount of food they eat. Old laboratory mice often die from cancer, however, the mice lacking interleukin-11 had far lower levels of the disease. And they showed improved muscle function, were leaner, had healthier fur and scored better on many measures of frailty. The treated mice also had stronger muscles, better lungs, skin, hearing and vision than their untreated counterparts

Interleukin-11 does have a role in the human body during early development. People are, very rarely, born unable to make it. If they cannot this alters how the bones in their skull fuse together, affects their joints, which can need surgery to correct, and how their teeth emerge. The researchers think that later in life, interleukin-11 plays a bad role in driving ageing. So the drug they have developed contains a manufactured antibody that attacks interleukin-11.

Professor Stuart Cook, further commented : “I try not to get too excited. There’s lots of snake oil out there, so I try to stick to the data”. He said that even though the trials have not yet been completed the data so far suggest that the drug is safe to take. He said that he “definitely” thought this drug would be worth trialling in humans saying that if it worked on the trial group he thought that the impact “would be transformative” and that he would even be prepared to take it himself.

Ilaria Bellantuono, professor of musculoskeletal ageing at the University of Sheffield, said: “Overall, the data seems solid, this is another potential therapy targeting a mechanism of ageing, which may benefit frailty.” However, he said there were still problems, including the lack of evidence in patients and the cost of making such drugs.

Videos released by Imperial showed untreated mice with greying patches on their fur, hair loss and weight gain, while the treated mice appeared sprightly with thick, glossy coats. The treated mice also lived for an average of 155 weeks, compared with 120 weeks in untreated mice.

Anissa Widjaja, an assistant professor at Duke-NUS Medical School in Singapore, which was working with Imperial, said: “Out of curiosity, I ran some experiments to check for IL-11 levels. From the readings, we could clearly see that the levels of IL-11 increased with age and that’s when we got really excited. We found these rising levels contribute to negative effects in the body, such as inflammation and preventing organs from healing and regenerating after injury. Although our work was done in mice, we hope that these findings will be highly relevant to human health, given that we have seen similar effects in studies of human cells and tissue. This research is an important step toward better understanding ageing and we have demonstrated, in mice, a therapy that could potentially extend healthy ageing by reducing frailty and the physiological manifestations of ageing.”

After the team had discovered that the protein causes inflammation and stopped tissues from regenerating properly, they wanted to see if switching it off could dial down the ageing process. After an initial experiment on genetically edited mice that had the gene producing IL-11 deleted, they found that this simple gene deletion extended the lives of the mice by more than 25 per cent on average. Next, 75-week-old mice (the equivalent of about 55 years in humans) were injected with the anti-IL-11 antibody to stop the effects of the IL-11 in the body. Prof Cook explained: “The mice had stronger muscles, they had better lungs, they had better skin, better hearing, better vision, multiple improvements. So not only can we do it by deleting the gene from birth, we can do it with a therapeutic drug given later in life which opens up this possibility of now taking this to humans. It may even prevent hair loss and greying.”

After the team had discovered that the protein causes inflammation and stopped tissues from regenerating properly, they wanted to see if switching it off could dial down the ageing process. After an initial experiment on genetically edited mice that had the gene producing IL-11 deleted, they found that this simple gene deletion extended the lives of the mice by more than 25 per cent on average. Next, 75-week-old mice (the equivalent of about 55 years in humans) were injected with the anti-IL-11 antibody to stop the effects of the IL-11 in the body. Prof Cook explained: “The mice had stronger muscles, they had better lungs, they had better skin, better hearing, better vision, multiple improvements. So not only can we do it by deleting the gene from birth, we can do it with a therapeutic drug given later in life which opens up this possibility of now taking this to humans. It may even prevent hair loss and greying.”

Dr Widjaja added: “Although our work was done in mice, we hope that these findings will be highly relevant to human health, given that we have seen similar effects in studies of human cells and tissues. This research is an important step toward better understanding ageing and we have demonstrated, in mice, a therapy that could potentially extend healthy ageing, by reducing frailty and the physiological manifestations of ageing.”

The research was published in Nature and partly funded by the Medical Research Council.